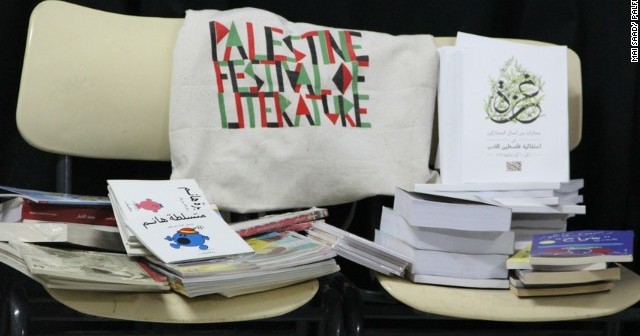

PalFest 2013: Beyond ‘the Crisis Narrative’ To Art & Experiment

The Palestine Festival of Literature is currently going on in several places at once:

The six-city festival kicked off on Friday: It opened in Gaza’s Mathaf Cultural Center with a big group of aspiring writers that broke out into three workshops led by: novelist Susan Abulhawa (on the evolution of the Palestinian narrative/s), journalist Ali Abunimah (on blogging and e-journalism), and editor-scholar Lina Attalah (on narrativizing Gaza ‘beyond crisis’).

The 2013 festival is, as novelist and organizer Ahdaf Soueif noted at Saturday’s Ramallah event, the first time that PalFest is occurring all across historic Palestine. “We are ignoring the artificial boundaries that are in place.”

The festival, however, is not wholly able to ignore them: One part of the festival is taking place in Gaza while another group of writers crossed from Jordan into the West Bank on Saturday morning and afternoon.

In her reflections on the first day of the Gaza side of the fest, Attalah noted that the Gazan story has long been framed as one of conflict and exceptionalism. “But,” she wrote, “to stroll in the old market, chat with vendors about what they sell, what comes ‘illegally’ from the tunnels with Egypt and what is permissibly acquired through the Israeli crossing, a sense of normalcy prevails.”

The crisis of Gaza, she writes, is “prevalent, visible, and haunting.” And yet she — and the emerging authors in her workshop — wanted to move away from, or beyond, the frame of crisis.

PalFest itself has often been narrated as a festival of crisis: checkpoints, borders, difficulties, tear gas. But, although the essential crisis shouldn’t be obscured, as well as other class and accessibility issues, the festival’s opening day in Ramallah was about art, hybridization, and experimentation.

South African writer Gillian Slovo read from her novel Red Dust, and composer Tareq Abboushi put together music both to accompany and to follow her reading from the book. She read two separate sections from the novel, one from the point of a torturer (Dirk) and the second from the point of view of a man he had tortured (Alex). Dimitri Mikelis played the oud, Maya Khaldi did vocals, and Boikutt produced what I called electronic soundscape and playwright Omar El-Khairy called “Atari beats.”

The amazing thing was that it worked: a South African courtroom drama, an oud, a sensual vocalist, an electronic soundscape.

Slovo said, after the event, that she had long been hesitant about doing something with novels and music; music, she said, has a much easier working relationship with poetry. She’d worried about “the power of music to drive the words into a place they shouldn’t be going.”

But the music, as Slovo read, framed and emphasized the text, heightening it. It was the first time I ever heard the sounds of nostalgic country music coming out of an oud (during Dirk’s section) and during Alex’s section it became both reflective and confrontational. But it never overwhelmed the words.

In the musical pieces that followed Slovo’s reading, the composer and musicians built on their translations of the text, transposing the novel into a different literary, linguistic, and audial register.

Attalah, in her post from Gaza, writes that, “Romanticizing crisis by talking about normalcy at the time of siege and occupation is currency and dangerous. But ….[t]alk about normalcy is about championing the everyday as a site of alternative arrangements to the oppressive status quo. It is about glorifying the ‘ordinary man… the common hero… the untold wanderer’ to use the language of Certeau.”

Normalcy can also be about glorifying the uncommonly beautiful music of Tareq Abboushi, Boikutt, Dimitri Mikelis, and Maya Khaldi and an uncommon way of experiencing prose and its (musical-literary) translation.

More from the festival’s opening days:

Susan Abulhawa’s reflections on the workshops and the Gazan singer in Arab Idol

Lina Attalah’s Beyond Crisis: Making Space for Laughter in Gaza

You must be logged in to post a comment Login