My First Hajj: It’s ‘Your Whole Life In Microcosm’

My Hajj was literally a set of circumstances pitted against a friend’s offer to go. Abdul Aziz, a 7 foot one British-Somali who reminded me of Big Bird when I saw him for the first time looming above the rank and file in the teachers’ lounge at King Saud University. People that tall had a hard time in Salat if they weren’t on the first row because of the clearance they needed for sajdah (prostration) behind the other worshipers.

I have never been too pleased with most Brits or Somalis perhaps because they seem to only have a modicum of his intelligence and chivalry. Most Brits had their own language distinct to British culture and therefore it comes off as some secret code for an American. They tend not to say anything directly but issue verdicts and opinions in catch phrases that are incomprehensible to the average American. Somalis on the other hand are very family oriented; antithesis to the American psyche emerging from single parents on double shifts while children watch themselves. Anytime I was around either group it was like being at a new year’s night party alone.

“Going to Hajj?’ he asked nonchalantly.

“Got too many bills to pay,” I whined. After a brief but financially catastrophic marriage in Indonesia and a small but tidy amount placed to purchase land in Yemen I was ‘pockets out’ broke although I wasn’t ordinarily dramatic enough to actually pull them out.

“No problem…you want to go, just put in for the leave and I’ll loan you the money,” he chuckled as if delivering a quip. Most people say you have to clear all your debts to make Hajj—yet this doesn’t explain why the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) asked about what he owed during the last Khubah (sermon) after his last Hajj. Besides, I was sure my debts I couldn’t pay before Abdul Aziz’s offer would be there upon my return.

Just like that, I was suddenly going to Hajj.

The group composed of the usual suspects from work, we decided we would meet in Jeddah—our Meekat, the station to don our ihrams. I cut my nails before I showered and changed—remembering my first and last Umrah (the minor Hajj they call it) somewhat more ordeal-ish when walking in the humidity of Mecca with long nails. Several of my traveling companions were fluent in Arabic—which seemed to put a great many people at ease.

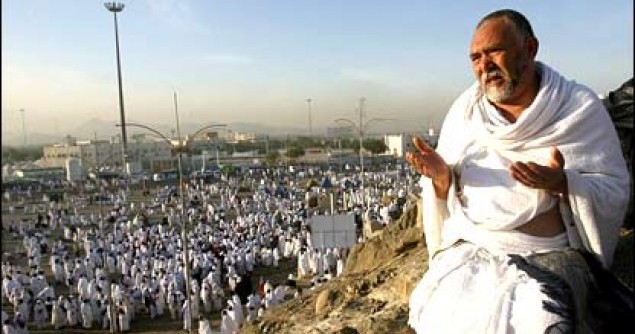

There were several people in our group that had done me a wrong turn, but I took it as a challenge to put aside my passionate dislike and sense of injury for what they did to me for the sake of my trip. They say Hajj is life’s journey in microcosm; that the trials are similitudes to those weathered in life. At the end of the day, everything comes from one source as a lesson to be learned rather than an issue honed and a score to settle.

Abdul Aziz, who had organized the group, arranged for a Hamlah (Hajj group) next to the Jamarat and even gave us manuals on what to do. We stayed in a tent enclosure under a modern concrete bridge specifically built to guide and manage the crowds to the site. Massive, it was draped between the piling and supports beneath the road constructed just for the walk to stone the devil, a major ritual of Hajj.

We all slept in groups in large compartments; matched up with nationalities of similar language and habit. I am flat footed; which made walking great distances nightmarishly painful—and every ritual (most involved walking) was like doing the two-step on hot coals. I had to take long rests after each ritual but consoled myself that I only had to do it once. If this Hajj were to expiate my sins, the pain was my atonement for all the things that made me unworthy to call myself Muslim, a believer, a man, a father and a human being.

That was two years ago and I am not certain how it changed me—just that it did.

My friend Abdullah Muslim told me that every once in awhile he thinks about a little detail from his first Hajj that brings some piece of knowledge to the forefront of his life. He told me years ago when he made his first Hajj; before all the modernization of the sacred precincts, there were streams that flowed through Mecca people would drink water from. Near the stream he saw a couple eating raw onions. His fellow travelers drank but he abstained. As they travel along the stream, he saw a spent diaper heavy enough to be anchored in the shadow part of the water. His friends later got sick.

“Later I found out that onions were a” medicine food” that have been used for hundreds of years to cure illnesses and purify the body,” he said. “Over the years, the memories of his first Hajj still teach and benefit me.”

I anticipate, or rather hope, the same will be true for me.

One Response to My First Hajj: It’s ‘Your Whole Life In Microcosm’

You must be logged in to post a comment Login