Saudi: Shock the Monkey, Question Convention

You do not need to be a paid-up Saudiologist to pick up Abdullah Al Jamili’s message in his article When Habits Become Faith, originally published in Saudi Arabia’s Arabic daily Al Madinah, subsequently republished by the Arab News.

You do not need to be a paid-up Saudiologist to pick up Abdullah Al Jamili’s message in his article When Habits Become Faith, originally published in Saudi Arabia’s Arabic daily Al Madinah, subsequently republished by the Arab News.

In his article he describes the famous experiment in which scientists conditioned monkeys to behave in a counter-intuitive way based on the experience of their peers without going through the experience themselves. He goes on to say:

This experiment is representative of life for some human communities in the Third World countries, especially those that are always led by tradition and fear of the unknown.

Many of our habits and practices are down to an inherited fanaticism, individuality of opinion and many other things instilled in us by our ancestors.

They have become our faith and our religion with which we kill ambitions and slaughter initiatives. Whoever tries to jump over these traditions, whether at an individual or social level, will be castigated and accused of being a heretic.

Many officials in our government departments worship these obsolete rules and regulations and would not dare to violate them. In fact, they will defend them without asking for the reason behind their application.

The traditions and norms of the people are usually governed by the circumstances of their time and place. Do we have to impose these obsolete rules on the new generations who are living in different circumstances? Is this part of an innate social conduct or are these rules imposed on them by some sectors of society in order to control them and keep them suppressed?

In order to build a better future, we have to unchain all the fetters of the past and also the illusion of what we call “the specialty of our society.”

Al Jalili takes pot shots – couched in cautious language – at several big targets.

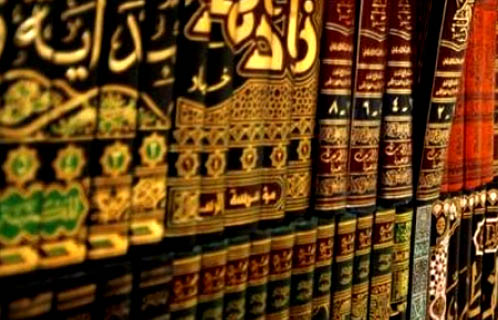

The first is the resistance of the social and religious conservatives to change – those who use a mixture of cultural tradition and interpretation of the Hadith – the reported acts and sayings of the Prophet Mohammed – to impose practices and social norms that the writer clearly thinks are inappropriate for the time we live in.

The second is the resistance of government officials to new ways of thinking – officials who cling to ways of doing things “because that’s the way we’ve always done it”.

Finally, he has a dig at his fellow citizens who believe that their country, as the custodian of the Holy Mosques and a nation blessed with abundant natural resources, is for these reasons special, and by implication superior to other nations.

Al Jamili’s frustration with conservatism is not unique to Saudis.

I was speaking to a Malaysian Muslim friend the other day. He told me that many young Muslims feel that state and society are continually telling them what they should not do, rather than what they should do. Muslims in Malaysia find themselves banned by law from doing things that are permitted to fellow citizens of other faiths. The state does not give its Muslim citizens the right to exercise their personal choice and act according to their own moral code in matters mandated by their religion, yet gives Christians, Buddhists and Hindus that opportunity. As a result, many Muslims, according to my friend, feel like third class citizens.

Which really goes to the heart of the matter – to what extent should the state and its institutions act as an intermediary between an individual and his or her conscience – and ultimately his or her Maker?

Most countries make laws whose purpose is to prevent citizens from harming themselves and others – physically and economically – and over centuries their legal systems have evolved into a minimalist and secular approach. Others enact laws for the same purpose, but use a moral code that goes much further in dictating acceptable behaviour. When that moral code is based on the word of God but subject to the interpretation of man, it is rarely the word of God that is questioned, but the way in which human interpretations of that word serve the higher purpose.

Which I think is what Al Jamili is talking about. Given King Abdullah’s recent allocation of increased funding to the religious establishment, there seems little chance that the fundamental relationship between Islam and the Saudi state will change any time soon.

Perhaps he will have more luck changing the mindset of those change-resistant government officials, and even in convincing his fellow-citizens that they are not so special.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login