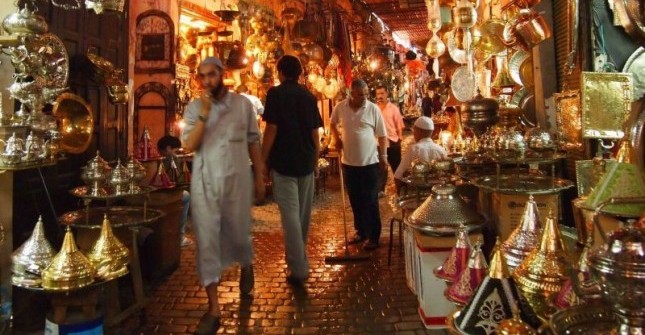

The Inter-Connected Magic of the Medina Souk

I was reading the other day that when a group of school kids were questioned about where they thought milk came from, most of them had no idea it came from a cow. A fridge shelf in Tesco seemed to be the main suspect. While it may be easy to snigger at the ignorance of modern children of some of the basics of life, it occurred to me that there are plenty of things that we take for granted, totally unaware of the story behind them.

Take the beautiful babouches, the soft leather slippers we see in rows lining walls in tiny shops in the souk. When you bought a pair did you ever think about where they came from? Probably not, but they certainly didn’t just appear thanks to the babouche fairy. Admittedly some are now being mass produced, but others are still made by hand, and their story, and that of much of the beautiful artistry we take home as gifts and souvenirs, is intricately woven into the whole fabric of life in the Medina.

This point was brought to mind when I was taking a walk through the Medina with Abdellatif Benhrima. Born and bred there, he knows the maze of alleys like the back of his hand, and as we wandered through the streets behind the Musee de Marrakech, he suddenly ducked into a vaguely disreputable-looking foundouk, one of the antiquated courtyards that provided both accommodation and sales space for travelling merchants for hundreds of years. Some of these foundouks have been restored as riads, but equally as many still maintain their original function as small workshops and commercial premises. Unfortunately, while some have been kept in reasonable condition, others suffer badly from years of neglect. It was strange to compare the world I’d stepped into of freshly-dyed skins drying in the sun, mopeds and beat up old handcarts with the décor of Le Foundouk, the chi-chi restaurant of choice of the tantalisingly rich, almost next door.

We went into a workshop tucked in a corner, no more than about three metres by one-and-a-half, where a man in white skull cap and thick brown corduroy jacket against the cold was carefully applying a soft white leather covering to the thicker leather of a belt. This was where, between the ages of twelve and fourteen, Abdellatif had worked, making slippers, belts and soft leather bags, sharing the space with four others.

In the inevitable ceremony of welcoming a friend, Abdellatif and I were offered tea. (And here I was introduced to one of the finer points of the Moroccan tea ceremony; if you are offered a glass of tea you are welcome, if you are asked to sit, chat and watch the tea being made, you are very welcome, as it’s an opportunity to chat and while away a few minutes while the tea is brewing.) While Abdellatif and his friend, Mustapha, caught up with their news I picked up a soft, beautifully embroidered shoulder bag in warm, rose-pink lying on the makeshift sofa beside me. I could see it draped across the shoulder of my granddaughter, and her smile as she received it. The bag wasn’t quite finished, it needed a strap and fastenings, but I asked how much it was.

‘You are here to take tea,’ said Mustapha, ‘not to buy something.’

As the guest I was offered the first sip from the single glass in Mustapha’s workshop, and when we’d each had a drink and the pot was being topped up for a second round, he climbed on his bike and rode off into the souk in search a strap so my granddaughter’s gift could be finished. A few minutes later, an elderly gentleman in a white djellaba appeared at the doorway, enquiring about the belts Mustapha had been working on. After exchanging a few pleasantries with Abdellatif, he took them and went on his way. He was the buckle man, who would punch the holes in the belt and fix the buckles. He would bring the rough leather belts to Mustapha for covering, and either sell the finished product himself or pass them on to someone else who had ordered them.

And that’s when the interconnectedness of the Medina struck home to me.

Mustapha would decide on the products he would make that week, whether to order or for him to sell direct to a shop. He would buy the few skins sufficient for his needs from the daily auction in the leather market and would then dye them himself and dry them in the courtyard of the foundouk or hand them over to someone to dye to his choice of colour. When the skins were prepared he would cut them to the pattern of the model he was making that week and then hand them to a woman who did the painstaking embroidery at home, as a way to supplement family income. When the pieces came back he would assemble them, then cycle to a cupboard-size shop to buy the silken cord that would make the shoulder strap, of exactly the right shade to match the dyed leather. He then covered the press stud fastenings in leather and fixed them in place.

One day each week he would gather his bags, or belts, or slippers together, and perhaps those of his family made in other miniscule workshops, and take them to his customers in the souks. If one shop didn’t buy them, another would. He would buy his vegetables from the food market and bread from the bakery that form part of the five ‘hearts’ of the quartier, his meat from the local butcher with a whole lamb hanging from a hook, and his groceries from one of the dozens of narrow cavernous shops almost within an arms-reach of his home. Everything contained within the walls of the Medina, each having his role to play in the highly organised chaos of life within the rose-pink walls.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login