Emirati Female Writers Finding Their Feet

The editorial that introduces the autumn 2011 issue of Banipal has an unusually defensive edge. The tone here is very different from the triumphant feeling of Banipal 40 (Libyan Fiction!), which followed on the heels of 39 (Modern Tunisian Literature!). In 42, editor Samuel Shimon takes pains to explain the choice of Emirati literature, as if someone behind him were whispering, “Emiratis! What do they write about? Their SUVs?”

The editorial that introduces the autumn 2011 issue of Banipal has an unusually defensive edge. The tone here is very different from the triumphant feeling of Banipal 40 (Libyan Fiction!), which followed on the heels of 39 (Modern Tunisian Literature!). In 42, editor Samuel Shimon takes pains to explain the choice of Emirati literature, as if someone behind him were whispering, “Emiratis! What do they write about? Their SUVs?”

Well, sure, there are BMWs and SUVs in these selections, as you might find tuktuks and taxis in a selection of Egyptian work (and Mercedes, Fiats, Hyundais, donkey carts, microbuses), and SUVs and Suburbans in U.S.-authored fiction.

And, sure, a general suspicion of money is well-warranted by this point in human history. But there is also interesting literary work being done in the Emirates.

The Emirati writers published in Banipal 42 are often critical of themselves and their project. Short story author Mariam al-Saedi says, in the issue (trans. Issa Boullata), “A conservative society closed in on itself, immersed in taboos, and ready to live within two colours only, white and black, will never produce a single real novel. The novel is not born in a suffocated, restricted society; and if it is ever written in such a society, it will be one of those novels which young women write desiring only to challenge society superficially and these are therefore novels without any literary value. Such novels are good for releasing pent-up feelings, nothing more.”

She continues: “The novel is life. How can you write about life if you basically don’t know it and haven’t really experienced it? The time for the novel has not yet arrived.”

It is worth noting that al-Saedi’s marker for novelist—unsuccessful though she may be—is a woman. As poet Adel Khozam notes in his short essay at the front of the issue (also trans. Dr. Boullata), “…there are many women in the Emirates who favour innovation, especially in poetry and short-story writing.”

While not all the selections from the female authors are more innovative than the men’s (stories by Fatima al-Mazrouei, Mona Abdelkader al-Ali, and Mariam al-Saedi were rather straightforward and Aisha al-Kaabi’s are full of too-easy “truths”), but, where I was struck, it was the women’s writing that struck me.

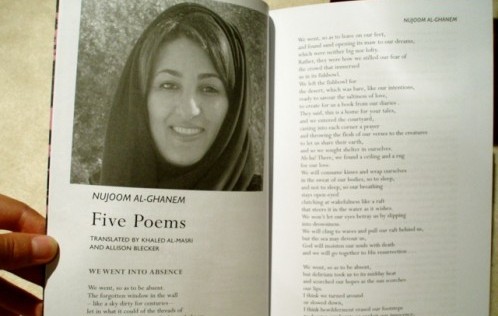

I was already expecting to be pulled in by the poetry of Nujoom al-Ghanem, trans. here as elsewhere by Khaled al-Masri, with its combination of the beautifully banal details of everyday life, plastic commercialism, and a surrealist spirituality. From “Morning’s First Desire”:

He gave himself a moon as a gift, so as to pass the night under its glow.

He painted the floor, the walls,

the bed and the table with milk.

He planted a white plastic Christmas tree

and hung it with white lights.

He bought cheese, yoghurt and bread

and sipped arak.

He clipped his nails and devoted himself to preparing

a list of his remaining dreams.

But it was not only al-Ghanem and her fellow female Khulood al-Mualla—poets I’m already primed to enjoy—who caught my attention. I also found a lovely, detailed story about marriage (and an allegory about power, if you like to read it that way) in Basema Younes’s “Silence,” trans. Ali Azeriah. The story could be built more carefully, and with a little more visceral description, but the suffocation of not-being-heard and not-being-recognized is captured here. I also took note of Ebtisam al-Mualla’s “A Fading Light,” the story of a privileged girl who will soon lose her sight, for its small details and affection for its characters, as well as Dhabiya Khamis’s “A Travelling Tale” for its willingness to criticize hypocrisy.

Read for yourself:

You must be logged in to post a comment Login