Egypt’s Revolution Reignited on Army Inaction

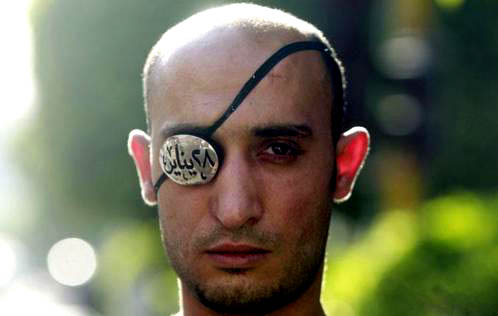

“I’d rather live blind with dignity than live with eyesight, but in humiliation.”

“I’d rather live blind with dignity than live with eyesight, but in humiliation.”

The inspiring words of now iconic Ahmad Harara, a young dentist and political activist known for his Arabic calligraphy eye patch emblazoned with “January 28”, a reminder of the “Day of Anger” when he lost his right eye, the day we all believed marked the beginning of the end of the old regime.

Today, his left eye is covered with a fresh patch commemorating November 19.

Another young man writes a telephone number on his arm “so they can reach my mother when they find the body,” he says.

Hundreds of others have been wounded with birdshot or rubber bullets which burnt through their clothes and skin, but they go right back into Tahrir Square as soon as they can stand up.

Over 23 have been killed, their bodies packed in Zeinhom morgue in a scene deplorably reminiscent of the darkest days of Egypt’s recent history, a history that is repeating itself much sooner than it should have.

The similarities between today and nine months ago are disturbing and poignant: state media is claiming that “unknown infiltrators” are attacking the police and protesters with teargas canisters; the Arab League chief is urging all political forces “to work for calm and return to the political process and move forward with the process of democratic change based on the principles of freedom, dignity and social justice”; analysts are condemning the excessive use of violence against peaceful protesters; and human rights groups are up in arms; the White Houses calls on all parties to exercise restraint.

Yet, what is happening today is different. The confrontation back then was between the police and the Egyptian people who braved the water cannon and hail of bullets knowing deep down inside that when push came to shove, Egypt’s valiant army will be on their side, tipping the balance against a 30-year tyranny that has trampled their dignity and shredded their humanity.

Today, the crisis of confidence in the army has reached its pinnacle, a process that began less than one month after Mubarak was ousted when SCAF ordered the violent dispersal of a Tahrir sit-in on March 9 and the revolting litany of police torture, military trials and virginity checks was set in motion under the false pretext of imposing law and order.

A high-ranking army official told reporters in an interview aired on Al Jazeera Mubashir that the army was deployed to “protect the police”, a statement that sums up the tragic turn that Egypt’s unfinished revolution has taken.

A 13-year-old boy was shot dead in Tahrir last night as amateur footage showed four central security policemen dragging a young woman from her hair and clothes across the ground and hitting her with a stick; as yet another shows five policemen taking turns to hit a protester with their truncheons, one of them deliberately targeting his head. In another video, a policeman says “I shot him in the eye”, as a nearby officer praises him for a job well done.

As protesters who witnessed the bloody Maspero crackdown of Oct. 9 had observed, police were out to seek revenge, not to protect public property and impose law and order. Had the rule of law been their motive, the pretext used to justify the illegal extension of the state of emergency, then the 12,000 military trials of civilians would have been an adequate deterrent of crime, effectively counteracting the effects of the security vacuum.

But the facts on the ground prove that this is far from the truth. On the contrary, while thousands of civilians have faced military tribunals which have also singled out activists who practice their legal right to freedom of expression to criticize SCAF, not a single policeman or army soldier has been seriously interrogated or convicted in relation to the hundreds of reported cases of police abuse before and after the uprising.

The indications are now unequivocal: the only reason why Egypt is in this state of flux, fear and fragmentation today is because SCAF has grossly mismanaged the transitional period in a way that betrays a lack of serious commitment to democracy and at the same time exposes SCAF’s intentions to puppeteer the political process.

SCAF clearly thinks of this uprising as a continuation of the army’s failed 1952 coup that brought nothing to this country but failure, humiliation and disappointment. It’s time the army generals woke up from their slumber: Tahrir is brimming, the fear barrier has collapsed and there is no turning back.

Rania Al Malky is the Chief Editor of Daily News Egypt, the regional publishing partner of the International Herald Tribune. Rania won the Chevening Fellowship, British Foreign and Commonwealth Office, in 2005, and the Graduate Merit Fellowship, from the American University in Cairo, 1996-1998.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login