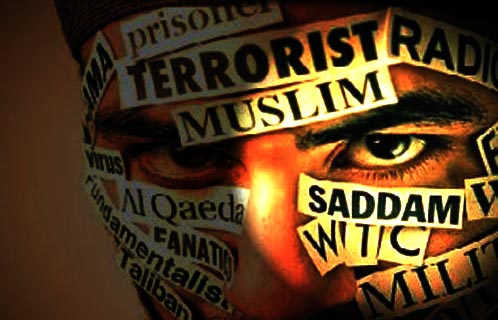

Islamaphobia and the Clash of Civilizations

Saudi Arabia’s Arab News has a number of columnists whom I, as a blogger and occasional columnist, admire for their humane and balanced views, and for the eloquence with which they express them. Tariq Al-Maeena, Dr Khalid Alnowaiser and Iman Kurdi are three who stand out. I have quoted the first two in previous posts on social issues in the Middle East.

Iman Kurdi, in today’s edition of the paper, has written a commentary on Baroness Warsi’s speech earlier this week. Warsi’s assertion that Islamophobia has passed the “dinner party acceptance test” in the UK has garnered widespread attention. Iman Kurdi’s article is called Islam and Dinner Party Test. Here’s an extract:

Warsi’s comments have received widespread backing among Muslims in Britain and elsewhere in Europe. What you hear most is that Muslims are being seen as different from the rest of society, that Islam is somehow incompatible with Western values, that Islam is under attack, all the thoughts that emanate from that good old phrase we’ve not heard in a while: Conflict of civilizations.

I think, however, that we need to be careful and to be weary of being oversensitive to criticism. Discussing Islam has passed the dinner party test. It has become a topical subject of conversation. Whereas once religion was considered unacceptable polite conversation, recent events have propelled it onto the world stage. People are naturally more interested in Islam and Muslims. Also Islamist terrorism is a reality and we cannot be surprised that it has dominated the agenda.

I would rather have people express their views openly and allow healthy argument, even if some of these views may be offensive to me, than the subject become so taboo that people don’t dare discuss it. Most of all, a distinction has to be made between criticism of Islam and Islamophobia. The two are not the same. People have a right to disagree with Muslim thinking, to be at odds with some of our beliefs and practices, to hold diagonally opposite views to ours. It is not their religion after all. That does not make them Islamophobes. When they discriminate against Muslims or label Muslims terrorists or blame Islam as a religion for acts of terrorism, that is Islamophobia. It exists, it is on the rise, but has it really become socially acceptable?

I would argue that in some circles the answer is yes. Particularly among supporters of the British National Party in the UK, and other far right European groups like Marine Le Pen’s National Front in France. But remember that for these political parties xenophobia is the staple diet. Islamophobia happens to be the the most convenient ingredient in the xenophobic recipe. In the past “blacks” and Jews have been the targets in the UK. In France, North African Arabs, Vietnamese and other immigrants from France’s former colonies have been the mutton in the pie. These days they’re still in the mixture, but take second place to Muslims.

Within the UK population in general, my perception is that people tend to focus on behaviour rather than faith itself. Behaviour associated with faith, such as dress, protective (many would say restrictive) attitudes towards women, is often as much to do with traditional cultures in countries from which ethnic groups originated. Look for example, at old ladies dressed in black in staunchly Christian countries such as Greece and Italy – traditional attitudes towards women in some areas of Southern Europe are not so different from those in many parts of the Middle East. Also consider homophobia in many African countries, which has been such a point of controversy within the Church of England.

An alternative test to Baroness Warsi’s dinner party construct is internet jokes about Muslims. I get lots of jokes from people of all social, political and religious hues. I don’t block the sources, because I find them to be an interesting social barometer. Jokes I receive about Muslims tend to bear out the distinction between faith and behaviour. Islamist terrorists are the most frequent subject, followed closely by burqas and niqabs. But I very rarely see offensive jokes about, say, Jews, Pakistanis or people of afro-caribbean descent.

This is only a personal impression. Some academic looking for a research project might find an analysis of internet jokes to be a fertile subject. If the internet had existed thirty years ago, I suspect that the joke traffic would have been very different.

What’s to do? Well, speaking of Britain, we’re a long way from latent or overt Islamophobia translating into repressive legislation specifically targetting Muslims. Yes, since 9/11, we have anti-terrorism laws that some would argue are used to suppress opinion. We have also introduced laws prohibiting incitement of religious hatred. But these laws are not just a weapon against radical Isamists – they can also be used to protect Muslims from the effects of Islamophobia.

In recent history, I would argue that Britain has a good record in dealing with extremism. In the 1930s Sir Oswald Mosley’s Nazi-inspired National Party failed to gain widespread traction. The more recent IRA terrorist campaign did not result in persecution of the Irish community in the UK mainland. And the current British National Party’s recent election results have not gained significantly from the noise they have generated.

So long as the threat of terrorism remains, fear will remain. If I was advising the UK government on a strategy to contain Islamophobia, it would be to fund and morally support efforts to communicate the distinction between faith and behaviour, and between religious observance and culture. To help Muslims explain the core of their faith rather than defend external manifestations seen by many as diversive. And to hold up role models who translate their core beliefs into actions that benefit society in general.

Am I being complacent when I say that a weary acceptance that terrorism is a fact of life in British society has entered the DNA of present generations? That the bombing of Britain in the Second World War, successive IRA campaigns and now atrocities such as the 2006 tube bombings have made us better able to cope than some other Western countries – the United States for example? That we try to get on with our lives despite the threats around us, and trust our govenments to deal with the threats as best they can? That in Britain at least, the tradition of tolerance will survive the current stress test? Maybe.

I just fear that we British will have many more compelling issues on our plates in years to come.

Here in the Middle East, I hope that the common humanity expressed in the voices of Tariq Al-Maeena, Khalid Alnowaiser and Iman Kurdi will find a wider audience both within and outside the region.

3 Responses to Islamaphobia and the Clash of Civilizations

You must be logged in to post a comment Login