The UAE and ‘Big Culture’: What Role For Expats?

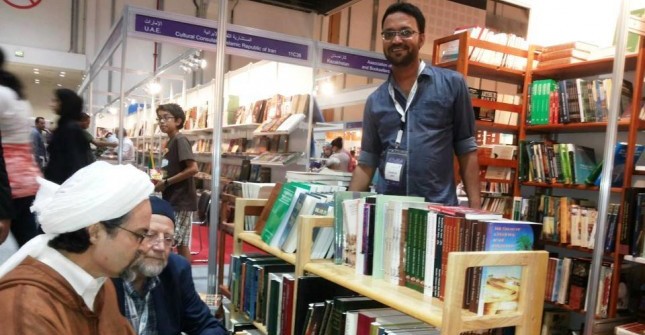

A week ago, I was at the Abu Dhabi International Book Fair:

As before, it was held inside the city’s large, overly air-conditioned national exhibition center. (Photographs here.) While my teeth chattered, I attended talks; I went to children’s-book readings and eavesdropped on professional events; I interviewed authors, publishers, and editors; when possible, I glanced through the stands and talked to booksellers.

The cultural lineup was as impressive as ever. A number of authors of global standing were at this year’s fair: Algerian Rachid Boudjedra, Icelandic Sjón, Lebanese-Canadian Rawi Hage, Ukranian Andrey Kurkov, Syrian Nihad Sirees, and more. There were also academics and thinkers of global importance, such as science writer Jim al-Khalil and scholar Ella Shohat; there were regional authors with powerful populist charm, notably Ahlam Mosteghanemi and Ibrahim Eissa. The professional events were diverse and often thoughtful.

This was my second time at the Abu Dhabi fair. It’s comparable in size, expense, and ambition to the other big UAE book fair, held in Sharjah each fall, but Abu Dhabi’s got a more international feel. Before attending this year’s fair, I wrote over at the Kenyon Review that the “Abu Dhabi Book Fair is a big, extravagant, exotic plant brought to the city as a joint venture between Abu Dhabi’s cultural authority and the Frankfurt Book Fair. It came into flower suddenly and dazzlingly in 2007, bloomed more brightly in each successive year, and now is fully managed by the Abu Dhabi Tourism and Cultural Authority. The fair could adapt, set down roots, and become a local plant, one that is a leader regionally and globally.” (Or, I added, it could slash away at the open discussions and free speech that allow book fairs to live and breathe.)

Now that I’ve returned from the fair, I’ve been reflecting on how difficult it is to say what “localization” and “roots” mean in a country that’s 90-percent non-Emirati. This 90 percent — of Pakistanis, Egyptians, French, Malaysians, Indians, Filipinos, Syrians, Lebanese, others — may contribute vibrantly to the country’s development. Yet they cannot, as things currently stand, be considered locals.

Most observers have problematized the UAE’s ethnic breakdown, and indeed the nation’s rulers are trying to change this “population problem.” According to a 2011 report in the Gulf News, the government’s strategy is to make Emiratis the majority (or at least around 40 percent) by 2021. However, even if this can really be achieved, the “foreigners” will continue to make up a large part of the country’s workers, lovers, and readers.

More and more, Emiratis are moving into meaningful positions in the country. Certainly, some Emiratization projects have benefited the country’s literary world. In the last few years, these schemes have encouraged more Emirati authors, illustrators, and publishers. The “Made in UAE” workshops, in partnership with Goethe-Institut, have brought new energy into the local children’s-book scene. But this Emiratization has been for creative and managerial work: It’s doubtful that the jobs of those who assembled the fair — those who were laying carpet and erecting last-minute displays at 2 a.m. the night before launch – will be Emiratized any time soon.

The “population problem” seems to be linked to one of the fair’s main stumbling blocks: attendance. Although the cultural events were well-conceived, major writers sometimes had just a handful of listeners, and many of these were their friends or colleagues. A few Egyptians jokingly suggested that this could be solved Gamal Abdel-Nasser-style, by busing laborers to the talks. The idea is absurd, but it nonetheless points to a question: Whose book fair is it?

On Friday, when the fair started late, I — along with a number of other journalists — was bused out to hear about the city’s Saadiyat project. This includes the Abu Dhabi Louvre (set to open in 2015), the Abu Dhabi Guggenheim (set to open in 2017), and the Zayed National Museum (in partnership with the British Museum, set to open in 2016). There was a great deal of sizzle and flash in the presentation, but I never really understood: Whose museums are they? Will the museum-goers be a generic global crowd of artists and art-tourists? Or will these museums be a meaningful part of “local” life?

In a op-ed published recently on CNN, commentator Parag Khanna writes that, for long-term sustainability, “UAE will have to transform itself from post-modern feudalism to an innovative stakeholdership model in which foreigners are accorded long-term residency rights, and both citizens and foreigners have meaningful rights as well as responsibilities.”

Certainly, meaningful rights and responsibilities are a good idea for everyone. But how do these semi-permanent foreigner-stakeholders — whether 90 percent of the country or 70 or 50 — participate in, and relate to, Big Culture?

You must be logged in to post a comment Login