The Silence of the Poets – And That Includes You, Adonis

In recent days, two very different views of poets and politics have appeared online.

In recent days, two very different views of poets and politics have appeared online.

In “Unfree Verse,” Youssef Rakha (himself a poet) argues that the earlier generation of ’60s poets were shackled to a particular ideological discourse, and asks: “To what extent could [Amal] Donqol – or [Mahmoud] Darwish – afford to write poetry for its own sake?”

He asserts that the real revolution in Arabic poetry came via the “we are not interested in big issues” nineties generation, which Rakha says has promoted a Nahda, or renaissance, in Arabic art.

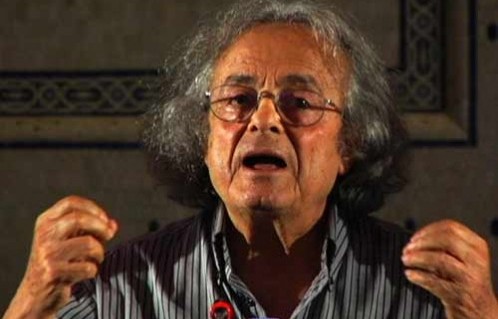

Meanwhile, over at Qantara in “The Silence of the Thinkers,” journalist Mona Naggar decries the awarding of the Goethe Prize to dis-engaged Syrian poet Adonis. Naggar criticizes the poet for not taking a clear position on ongoing protests in Syria. And, because of his political squishy-squashiness, she says he should not receive the Goethe award for excellence in literature.

Naggar goes on to say, of Arab writers, that “none of them has played an active role in the protests and revolutions”: neither in Avenue Bourgiba nor in Tahrir nor anywhere in Syria. This is a peculiar and incorrect assertion. But the essence of Naggar’s argument remains the same: Adonis should not be receiving a prestigious German cultural prize just now. She says: “The Arab Spring really didn’t deserve this!”

There’s no doubt that Adonis has fashioned himself as a cultural and political commentator as well as a poet, and that his unwillingness to take a position on Syrian protests is open for engaged criticism. Naggar writes:

The young Syrian writer Maha Hassan brings criticism of Adonis to a head when she calls on him to utilise his last opportunity and adopt a clear position on the Syrian revolution. In an article for the national daily newspaper Al-Hayat, Hassan writes: “You must be clearer, more robust and more exact in your statements on events in Syria. You must take a stance, say something about the Syrian blood that has been spilled!”

Does this mean that the Germans should be careful not to give Adonis a literary prize?

Meanwhile, over at the Arabophile, Rakha is arguing for greater freedom for the Arab poet: freedom from an ideological line. And that this freedom, rather than the engaged politics of the sixties poets, better serves Egyptians’ struggle for independence.

Meanwhile, at the Kenyon Review Online (KRO), Iraqi poet Sinan Antoon says that all kinds of poetry have been engaged in protests:

Contrary to all the brouhaha about Twitter and Facebook, what energized people in Tunisia and Egypt and elsewhere, aside from sociopolitical grievances and an accumulation of pain and anger, was a famous line of poetry by a Tunisian poet, al-Shabbi. Poetry, novels, and popular culture have chronicled and encapsulated the struggle of peoples against colonial rule and later, against postcolonial monarchies and dictatorships, so the poems, vignettes, and quotes from novels were all there in the collective unconscious. Verses were spontaneously deployed in chants and slogans and disseminated in clips. The revolution introduced new songs, chants, and tropes, but it refocused attention on an already existing, rich and living archive.

Also on the KRO, from me: A Review of Adonis: Selected Poems

You must be logged in to post a comment Login