Why the U.S. Should Push for Democracy in Egypt

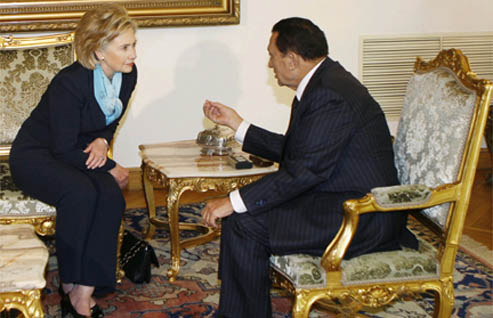

Human rights were glaringly absent from U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s agenda when she recently met with Egyptian Foreign Minister Ahmed Aboul Gheit ahead of Egypt’s Nov. 28 parliamentary elections. The silence is noteworthy, given Cairo’s suppression of the political opposition in advance of the elections as well as its overall dismal human rights record.

The Obama administration fears that Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak will respond to criticism by withdrawing both political support for the stumbling Israeli-Palestinian peace process and logistical support for U.S. military operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. The administration is also concerned that criticism would boost the Muslim Brotherhood, Egypt’s popular Islamist opposition group. Finally, should Egypt simply reject the criticism, it could paint President Barack Obama as too weak to influence one of the United States’ closest allies and a major recipient of U.S. aid.

Apparently testing the waters, State Department spokesman P. J. Crowley called on Egypt in a written statement to allow peaceful political gatherings and open media coverage, and to admit international election observers. Egypt immediately rejected the call, saying it has a system of judges and other safeguards in place to monitor the fairness of the elections and that the government has issued guidelines for free and fair media coverage of the campaign.

To be sure, repression of the opposition, intimidation and control of the media, and electoral restrictions virtually guarantee that Mubarak’s ruling National Democratic Party will win the elections. But for the U.S., the long-term risks of being perceived as perpetuating authoritarian rule in Egypt and elsewhere in the Arab world may well outweigh the short-term benefits of turning a blind eye to flagrant human-rights violations and measures that stymie democratic development.

The Obama administration’s concerns appear rooted more in a long-standing U.S. reluctance to rock the boat in a volatile, geostrategically crucial part of the world than in a realistic cost-benefit analysis. In fact, the United States may have more leverage than administration officials assume.

Egypt has a vested interest in continued support of U.S. policy in the greater Middle East. And by backtracking on support for either the Israeli-Palestinian peace process or logistical and intelligence assistance for U.S. military operations in the region, Egypt would risk the disfavor of the U.S. Congress, which signs off on Egypt’s substantial annual aid package. The Egyptian government uses much of that aid to strengthen its domestic security and its ability to confront domestic popular movements. Jeopardizing Washington’s largesse could spark concern in the Egyptian military over the future of its prerogatives, at a time when speculation about who will succeed Mubarak is already raising concerns over continuity in Cairo. The Egyptians are also unlikely to risk their success earlier this year in getting USAID to fund only nongovernmental organizations that are officially recognized and authorized by the government, ensuring that Cairo controls all U.S. democracy and human-rights assistance to Egyptian NGOs.

Fears that Egypt’s Islamists would benefit from a U.S. focus on democracy and human rights, though valid, are also exaggerated. Electoral conditions for the Muslim Brotherhood have significantly deteriorated since the 2005 elections. Egypt’s state of emergency has been extended, and constitutional amendments were enacted to eliminate full judicial supervision of elections and outlaw political activity involving a “religious point of reference.” U.S. criticism of such authoritarian measures would indeed echo and bolster the Brotherhood’s own denunciations of the regime. Moreover, the Islamists would probably perform well in a more open electoral environment that was not designed to stymie the regime’s opponents. But the Brotherhood has been substantially weakened, with many of its leaders in prison, one-quarter of its candidates barred from standing as candidates and its main electoral slogan — “Islam is the solution” — declared illegal. So U.S. pressure on Cairo is unlikely to result in any immediate gains.

In the Obama administration’s calculations, this month’s elections are likely to be of only moderate importance. Looming large in the background are Egypt’s presidential elections scheduled for next year, which could potentially change the country’s political landscape. Speculation is rife about whether Mubarak, who is 82 and ailing, will run for a sixth six-year term or whether he will instead push his son Gamal or his intelligence chief Omar Sulaiman into office. If Mubarak does opt for re-election, few believe that he would be able to serve another full term.

Despite the dynastic stigma that Gamal Mubarak would bear in the event he did emerge as Egypt’s next head of state, his presidency would constitute a break in Egypt’s post-revolution tradition of having military leaders run the government. Some officials fear that a focus on democracy and human rights now would complicate things later for Gamal, who would not enjoy the kind of support from the military that his father has.

Yet, that may be one reason why this is the right time to criticize Egypt’s human rights record and its stifling of democracy. By publicly focusing on the issue, Obama would shape debate in Egypt prior to a changing of the guard along the Nile, encouraging democracy and human-rights activists and altering a widespread perception in Egypt and the rest of the Arab world that the United States favors authoritarian rule.

Instead of invoking threats or sanctions if Egypt fails to clean up its act, Obama could avoid setting himself up for failure as well as criticism that he is unable to impose his will by taking a page from former President George W. Bush’s playbook. By positioning his statements as a policy goal to be achieved over time, Obama, like Bush, would shape debate in Egypt, encourage activists and influence perceptions of the United States — all of which would serve long-term U.S. interests.

All in all, the United States has more to gain by nudging the Egyptian and Arab debate toward an embrace of democracy and human rights — and more to lose by maintaining a policy that so far has primarily identified Washington with repressive, corrupt regimes, significantly tarnishing its image.

The Turbulent World of Middle East Soccer is the progeny of James M. Dorsey, a senior fellow at Nanyang Technological University’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies. Soccer in the Middle East and North Africa is played as much on as off the pitch. Stadiums are a symbol of the battle for political freedom; economic opportunity; ethnic, religious and national identity; and gender rights. Alongside the mosque, the stadium was until the Arab revolt erupted in late 2010 the only alternative public space for venting pent-up anger and frustration. Soccer has its own unique thrill – a high-stakes game of cat and mouse between militants and security forces and a struggle for a trophy grander than the FIFA World Cup: the future of a region.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login