Romney’s Middle East Team: Same Old, Same Old

THE US government may have a penchant for adventures on foreign soil and blind loyalty to Israel, but the American people generally have isolationist tendencies.

The Republican Party pretty much feels the same way, offering little in a coherent foreign policy or even understanding the Arab Spring’s impact on the Middle East. Other than the Republican Party’s unwavering support for Israel and lip service for a two-state solution with Palestine, conservatives can offer no single Middle East foreign policy position of substance.

A recent Washington Post-ABC News poll showed that just 1 percent of Americans considered foreign policy — including national security and terrorism — the most important issue in the 2012 presidential election. Republicans are taking advantage of this disinterest.

Presumptive Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney tentatively stepped up to the plate and offered the obvious: Support Israel, consult with military commanders on the direction of the Afghanistan war, oppose Iran developing nuclear weapons and increase defense spending.

As the November election draws closer Romney must flesh out these vague pronouncements. Yet Middle East leaders have much to worry about if the foreign policy team Romney assembled late last year is any indication of what’s to come should he become president.

Romney attempted to demonstrate a serious effort to formulate a Middle East foreign policy that protects US interests and further the cause of spreading democracy. However, all indications point to forsaking President Obama’s pragmatic approach by returning to a neoconservative ideology. That didn’t work out so well for the Bush II administration. And the stakes are much higher with Syria in a free fall and Egypt’s elections in shambles.

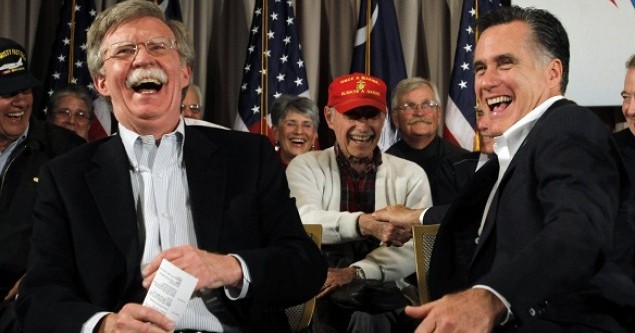

Romney’s foreign policy team reads like a who’s who from the Bush administration: Eric Edelman, Bush’s Undersecretary of Defense for Policy; Michael Chertoff, former Secretary of Homeland Security; Roger Zakheim, former Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense; Mary Beth Long, once the Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs; Meghan O’Sullivan, a Deputy National Security Adviser for Iraq and Afghanistan; and perhaps the most conservative of them all, John Bolton, the former US ambassador to the United Nations.

The only Arab on the team is Walid Phares, a Lebanese Christian. He writes for the ultra-conservative anti-Muslim online publications Frontpage Magazine and Family Security Matters and the right-wing newspaper Washington Times.

Phares’ appointment by Romney is particularly troublesome. Phares, who was involved in extremist Lebanese militia groups, has a history of claiming that jihadists are infiltrating America’s mosques and educational institutions and are simply waiting to strike. He described the right-wing militia group Guardians of Cedars, with its slogan “Kill a Palestinian and you shall enter Heaven,” as moral fighters. This is a man who has Romney’s ear. Romney can no longer claim the “moderate” Republican mantle, but is instead a potential president who feels that people like Phares have the bona fides to help shape US foreign policy in the Middle East.

Phares is only a symptom of what is wrong with the Republican Party’s approach from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to the current events in Syria. Romney simply adopted the Reagan-era philosophy of “Israel first, Israel always” and “we don’t negotiate with terrorists” by refusing to engage the democratically elected Hamas.

And for a presidential candidate who questions the competence of Obama’s handling of Syria, Romney for now doesn’t stray far from the official policy of the White House. While Obama has made it clear that he opposes military intervention, the administration remains in close contact with Syrian opposition forces to pass on information to Gulf countries gauging events on the ground and the opposition’s capability against President Bashar Assad.

Romney last month offered a similar approach by suggesting the US “should work with partners to arm the opposition so they can defend themselves.” Is this the best Romney’s foreign policy advisers can do by mimicking Obama’s position? Those advisers may be playing it safe on the campaign trail, but once in the White House they may find nation building too hard to resist.

Obama learned that despite his 2008 campaign rhetoric the hard truths of realpolitik push aside ideological dreams. Bush II found out the hard way and it cost thousands of lives.

By trusting foreign policy issues to ideologues, Romney could very well return the US to Bush-era misadventures. When the November election heats up after the summer, Romney will have much explaining to do why a foreign policy team full of neoconservatives is the best way to engage Middle East leaders.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login