ISyria’s ‘e-Revolution’: It’s A Constant Game of ‘Cat and Mouse’

The Syrian uprising, more than any of this year’s Arab revolutions, is being fought online as well as on the ground. Supporters of both the revolution and the regime are using increasingly vicious methods to embarrass and threaten their opponents online.

The Syrian uprising, more than any of this year’s Arab revolutions, is being fought online as well as on the ground. Supporters of both the revolution and the regime are using increasingly vicious methods to embarrass and threaten their opponents online.

The Syrian government’s relationship with the internet has been an odd one. Until President Bashar al-Assad came to power in 2000, his only public role had been as head of the Syrian Computer Society. Upon assuming office, he promised to open up the country to the world. This was the Damascus Spring: satellite dishes proliferated, and internet cafes opened in the major cities.

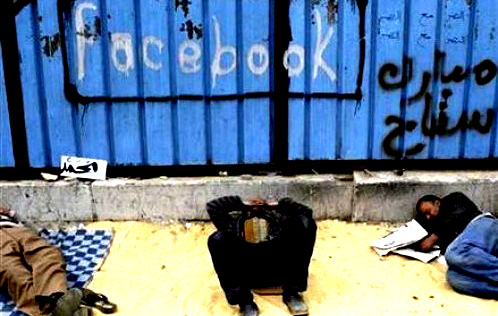

Not long afterwards, the rollback began. Political dissidents started getting arrested, and in the online world, restrictions came from nowhere. Hotmail was banned (which was difficult to monitor at the time due to its encryption), and then access to Yahoo! Mail was blocked. Hotmail was opened up again. In 2008 Facebook was blocked. Then YouTube. This revolving door of restrictions continued for years, with most internet users accessing these sites via proxies when banned by the state.

Something strange happened last February. With the Arab Spring in full swing, and rumblings of trouble in Damascus, Facebook and YouTube were suddenly unblocked. It seemed like a sign that the regime was opening up, but in fact, it just made it easier for the authorities to monitor what activists and civilians were up to.

Although Syria has an extremely low internet penetration rate (fewer than one-in-five Syrians is online),1 it has one of the world’s largest exiled populations. Syrians scattered across the world are helping their fellow citizens back home tell their story to the world. These internet users have taken on the role normally filled by traditional journalists.

The Syrian regime has always been wary of the mainstream media, controlling their every move within the country. When protests began in March, the restrictions became more pervasive. When Al Jazeera was accused of bias, its Syrian-born journalists were reportedly harassed and threatened until they quit their jobs with the broadcaster.

Other journalists have been arrested and kicked out of the country. Despite promises to open up to foreign reporters, the international media have had to rely on an increasingly sophisticated activist-run network, feeding stories from Syria. What started out as protestors filming demonstrations on their mobile phones and uploading to YouTube has grown into something altogether more professional. After the government began slowing down internet connections on Fridays (the weekly day of protest), Syrian activists based abroad have resorted to smuggling satellite phones into the country.The authorities reacted by threatening anyone caught in possession of one of these devices to eleven years in jail.

While the opposition has used new technology to fill the information gap, the authorities used old methods – threats and internet shutdowns – to block them. YouTube clips were still appearing on Al Jazeera and others, however, and the authorities realised they were losing the online battle. The technophobic regime realised it had to fight fire with fire.

The authorities, and their supporters, began to flood Twitter with irrelevant, automated messages, all tagged with #Syria. Anyone searching for news about Syria would end up being presented with links to old football scores and photographs from the country. Twitter reportedly responded by filtering out the Syrian spambots.

Since then, government supporters have become more organised, forming the Syrian Electronic Army. In a speech in June, they even received presidential backing. The Army has targeted foreign politicians and celebrities who have criticised the Syrian regime, hacking into their websites and putting up brazen messages of support for Bashar al-Assad. Most recently, they targeted the site of US-based Syrian singer Malek Jandali. In April, Jandali composed a song called Watani Ana (I am my homeland) and has been an outspoken supporter of human rights. His family was reportedly attacked in retaliation,1 and more recently, his website was hacked. On it the SEA put up a message accusing him of being ungrateful for the support the Syrian authorities have given him.

The activists hit back by hacking government websites. In the most high-profile attack, the Ministry of Defence site was taken down, replaced by a message of support to the Syrian people, and a warning that soldiers could face charges of treason. That attack was claimed by the international hacking group, Anonymous.

“Online, I would say the opposition is winning in that they’ve received massive support from the hacker community,” says Jillian York, Director for International Freedom of Expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation. But do these electronic catfights actually achieve anything? “At this point, I’d say no,” she says. “A couple of months ago when Syria wasn’t in the news constantly, I think it helped in the sense that it kept the world – especially other activists whose attention was on Egypt or Bahrain – tied to Syria.”

As well as their revenge attacks, activists also successfully pushed for alleged members of the SEA to be sanctioned. And they encouraged the EU and US to impose embargoes on the Syrian regime to limit its ability to buy spying technologies. A number of Western companies have been accused of supplying equipment and software to help authorities track the online work of activists.

Citizen reporters have been forced into using anonymising tools, some of which can be highly effective, but none is 100 per cent safe. It is a cat and mouse battle between the latest spy technology bought by the regime, and the latest encryption software downloaded by the activists.

Perversely, the technology sanctions, which are meant to help the opposition work more freely online, may be doing more harm than good. “Sanctions on technology really do hurt activists,” says York. “Regimes can easily circumvent the rules, as we’ve seen, but activists have a hard time getting hold of certain tools, while other tasks, like buying Skype credits, are virtually impossible.”

What started out as a battle between revolutionary hackers and the Syrian Electronic Army is now beginning to spread. Twitter users are reporting receiving hate mail and threats because they are perceived to support the wrong side. In one particularly nasty incident, Al Jazeera English journalist Dima Khatib, a reporter who has been banned from entering Syria, was harassed online and accused of being a regime lackey. The reason? She refused to back the #Nato4Syria Twitter campaign that called for foreign military intervention in the country.

In this electronic war, supporters of both sides have stopped listening to each other, turning to accusations and online hate-campaigns. It is this polarisation that will make post-conflict reconciliation challenging.

Neither the activists, nor the government, is going to deal a decisive blow via the internet. But they will make it harder for the other side to get their story out of what is becoming one of the world’s most isolated countries.

This article first appeared in ‘Near East Quarterly’

You must be logged in to post a comment Login