The Arabic Novel: A New Form of Criticism Required?

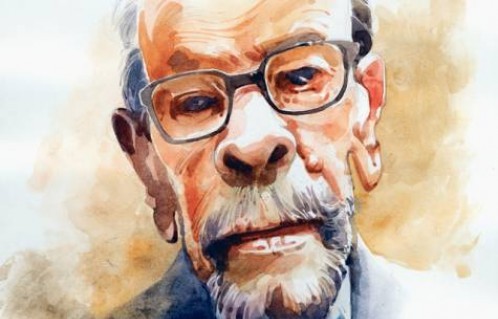

Fakhri Saleh—former IPAF and Mahfouz Medal judge and current al-Hayat columnist—has a short piece in this week’s Qantara arguing that Arabic literature requires a different, de-Orientalized sort of literary criticism.

Saleh makes the very easy point that Naguib Mahfouz (for instance) is not the Arabic “Balzac, nor a Galsworthy or an Emile Zola, or even a Thomas Mann.” Instead he likens Mahfouz to al-Jahiz.

But this is not a different sort of literary criticism; it’s just a brushing-off of silly dust-jacket equivalencies. As M.A. Orthofer notes over at The Complete Review, none of the aforementioned Western authors had Mahfouz’s range. And yes, you never do hear that “Honoré de Balzac is the French Mahfouz.”

Saleh goes on to state: The Arabic novel is not an imitation of the European novel. It lived in the shadow of the genre that flourished in sixteenth-century Europe, but it has its own history and development. Even the term riwaya, an equivalent of the term novel, does not have the same denotation. It means ‘narration’, ‘telling’, and it has a very direct relation to tale-telling in Arabic literary tradition.

It’s a good jumping-off point, but then Saleh does not really jump. He dips a toe into Emile Habibi’s The Pessoptimist, which he says draws on Quranic and other traditions, and another toe into Gamal al-Ghitani’s Zayni Barakat. But he doesn’t explore further. He doesn’t even follow up on the differences between riwaya and novel (new, interesting, shocking).

How do these differing traditions create different sets of contemporary cultural markers? How do they engender a different way of saying which works are “great” and which are not? How do they open up different spaces for criticism, different ways in which we can learn who we are through literature?

You must be logged in to post a comment Login