Tunisia – Battle moves to Media for Hearts & Minds

Three minutes into Zine el-Abdine Ben Ali’s speech on the two weeks of protests in his country, his phone rang. Already moving through his address in maladroit prose, the president became visibly more stiff and uncomfortable as a cell phone rang through several sections of his speech. He leaned inward, clasped his hands together, extended his arms out — palms down on a wide desk — and then leaned back again. It seemed as if Ben Ali believed that by moving his mouth toward the cluster of microphones sitting in front of him he could drown out the generic ring-tone chirping in the background. The mysterious phone phone call has become the butt of many jokes among Tunisians (and other Arabs).

He had spent most of the first portion of the speech outlining his sympathy for the unemployed and recent and historical achievements by the state in education and human development, citing recognition from the United Nations and its specialized agencies as “the embodiment of a fundamental choice consistent in our policy toward building an educated population.” The phone began to ring as he discussed “dialogue” between various social elements to consolidate “gains and achievements, particularly harmony, security and stability” while not exaggerating the impact on particular events. The ringing went on during this choice passage:

Also, it is unacceptable for a minority of extremists and provocateurs, against the interests of their country, to use violence and rioting in the streets as a means of expression, whatever the form in a state of laws such as ours. This gives a negative and un-civil appearance, creating a distorted picture of our country hindering investors and tourists, reflecting on the job creation we need to reduce unemployment.

It continued to ring into Ben Ali’s fourth point:

[. . .] We reaffirm the need to respect freedom of opinion and expression and will ensure their consolidation in law and in practice and we respect any position if it is expressed within the framework of compliance with the law, rules and ethics of dialogue.

Dialogue has become a rally word for government partisans. A Tunisian active in the ruling RCD party’s youth section admitted to this blogger that their “messaging will rely on this point. If there are people with complaints they can do this peacefully, they do not need demonstrations and violence.” A variety of like-minded Facebook groups coming from this perspective are now active. The young people in the streets would surely contest their primary assumptions and characterizations of their behavior. While Ben Ali visited Mohamed Bouazizi in the hospital and met with the families of other young men from Sidi Bouzid with glossy pictures distributed to the press.

“Enough of the violence! Talk.”

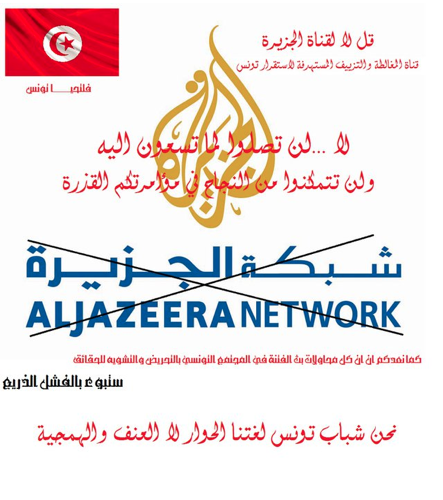

Like the president, these groups’ ring-leaders believe the whole affair has been exaggerated. Opportunistic opposition elements and a shameless Al-Jazeera, they seem to say, have blown the whole thing out of proportion and are damaging Tunisia’s international reputation, as the image below (taken from one such group) shows.

The protestors, who come from a variety of backgrounds, would likely point to something more like the image below and here (and the testimony here) as a reason for the protests’ spread and sustainment.

Al-Jazeera Arabic and English have covered the protests, using the limited footage available. Their websites feature articles on the protests that in parts directly contradict the official narrative. Other news agencies, especially the wire services and the LA Times, have picked it up as well, although the latter has kept most of its critical reporting on its MENA blog, “Babylon and Beyond” (the LA Times also published this interesting op-ed in April). Stringers from the wire services often appear to hold back in their reporting on the riots and demonstrations, likely for fear of reprisal from the security forces. Mainline north American and European newspapers have not covered the story in depth. The key American papers like New York Times and Washington Post, for instance have very little coverage of any of the Sidi Bouzid events or their aftermath. Le Monde and Figaro, for what should be obvious reasons have given more coverage in recent days. Brian Whitaker at the Guardian has followed the disturbances with his typical skill and insight. By accusing the foreign media of stoking and exaggerating the protests, Ben Ali and his supporters end up looking like their confidence has been shaken by a “minority of extremists” rather than the stewards of a rapidly advancing society where dissent is hard to find not because of a tightly managed police but by fully bellies and “moderation”. Round the world, there has been relatively little coverage of the Sidi Bouzid events, mainly because the government’s media blackout has been effective; that has not meant that the protests have stopped or that the government has been successful in placating the crowds. Word has gotten out, though, as have images and videos. The Chinese media have even covered the protests.

Al-Jazeera Arabic and English have covered the protests, using the limited footage available. Their websites feature articles on the protests that in parts directly contradict the official narrative. Other news agencies, especially the wire services and the LA Times, have picked it up as well, although the latter has kept most of its critical reporting on its MENA blog, “Babylon and Beyond” (the LA Times also published this interesting op-ed in April). Stringers from the wire services often appear to hold back in their reporting on the riots and demonstrations, likely for fear of reprisal from the security forces. Mainline north American and European newspapers have not covered the story in depth. The key American papers like New York Times and Washington Post, for instance have very little coverage of any of the Sidi Bouzid events or their aftermath. Le Monde and Figaro, for what should be obvious reasons have given more coverage in recent days. Brian Whitaker at the Guardian has followed the disturbances with his typical skill and insight. By accusing the foreign media of stoking and exaggerating the protests, Ben Ali and his supporters end up looking like their confidence has been shaken by a “minority of extremists” rather than the stewards of a rapidly advancing society where dissent is hard to find not because of a tightly managed police but by fully bellies and “moderation”. Round the world, there has been relatively little coverage of the Sidi Bouzid events, mainly because the government’s media blackout has been effective; that has not meant that the protests have stopped or that the government has been successful in placating the crowds. Word has gotten out, though, as have images and videos. The Chinese media have even covered the protests.

Though many of the North African states have “liberalized” their economies in the last ten to twenty years — often achieving impressive growth rates and increases in living standards — development has often been conspicuously uneven and official responses callus. Corruption, favoritism and nepotism have made privatization and foreign investment difficult for young people without the right connections to take advantage of liberalization. Elite handling of these development gaps has frequently relied on putting the lid down on dissent — hard. Protests like the ones at Sidi Bouzid, and now Tunis and elsewhere, are common in Algeria. Youth protests shut down the roads into Baraki, a suburb of Algiers, yesterday. Other such protests occur almost weekly to an extend where only the most most violent make it to the newspapers.

In the last five years when economic growth has increased in North Africa, youth riots and political protest have become increasingly common and notable. The LA Times piece mentioned above is useful in that it points out the structural problems in the Tunisian economy that make it difficult for the country’s well educated youth to capitalize on their skills because of the country’s reliance on European tourism and other low-skilled sectors. Like youths in other Arab societies with “benevolent” dictators and beautiful landscapes, many educated Tunisians find themselves prisoners of their country’s “comparative advantages.” While youth frequently suffer from economic and social problems disproportionately in Arab societies (due to their large numbers), they are almost never alone in these hardships.

Tunisia’s demonstrations are not restricted to angry youths; 300 lawyers protested in Tunis to protest government policy and show solidarity with the unemployed at Sidi Bouzid (some were arrested). Others who have spoken out have been arrested. A trade union demonstrated outside the Ministry of Education building and the government blacked a rally at Gafsa. Government forces have reportedly begun night raids against union and opposition organizers. The constituency and issue pallet for the demonstrations is expanding.

Brian Whitaker writes:

[. . .] we are seeing the breakdown of a long-standing devil’s compact where, in return for submitting to life under a dictatorship, people’s economic and welfare needs are supposedly taken care of by the state.

Officially, unemployment levels in Tunisia are around 13% though in reality they may be higher – especially among university graduates. According to one recent study, 25% of male graduates and 44% of female graduates in Sidi Bouzid are without jobs. In effect, they are victims of an educational system that has succeeded in providing them with qualifications that can’t be used and expectations that can’t be met.

The regime also seems to have overdone its trumpeting of Tunisia’s economic progress. If those claims are true, people ask, what happened to the money? One answer they give is that it has gone into the pockets of the Ben Ali family and their associates.

“The First Lady,” Dr Larbi Sadiki of Exeter university wrote the other day, “is almost the Philippines’ Imelda Marcos incarnate. But instead of shoes, Madame Leila collects villas, real estate and bank accounts”. Then there’s the president’s son-in-law and possible successor, Mohamed Sakhr el-Matri whose OTT lifestyle and business interestswere eloquently described, courtesy of WikiLeaks, by the US ambassador.

As stated previously, these riots are important because they challenge the dominant discourse on Tunisia’s politics (or lack there of) in western writing and reporting. Tunisia is by far among the most politically stable countries in North Africa and arguably the one with the healthiest economies. But this is all relative to its neighbors and must be considered in the regional context. If things are going the way they are in Tunisia, what does this mean for other geriatric regimes on the verge of power transitions? What impact will these have, if any at all, on how emerging Arab leaders in Egypt, Algeria, Libya and elsewhere look at their people?

Also be sure to listen to “Music of the Revolution” here and here. See here for a very comprehensive account of the events [Arabic, French].

You must be logged in to post a comment Login